HTML (Hypertext Markup Language) is the coding language used to describe the content of websites.

HTML has no look—it’s only purpose is to describe the meaning, the semantics, of the content.

HTML is plain text

HTML documents aren’t anything special, they’re just plain old text files. So plain and old that you could open an HTML file on a computer from the 70s.

The only thing that turns a plain text HTML file into a website is the web browser. The browser takes that text, parses it, figures out what the tags are that you’ve chosen and displays the website.

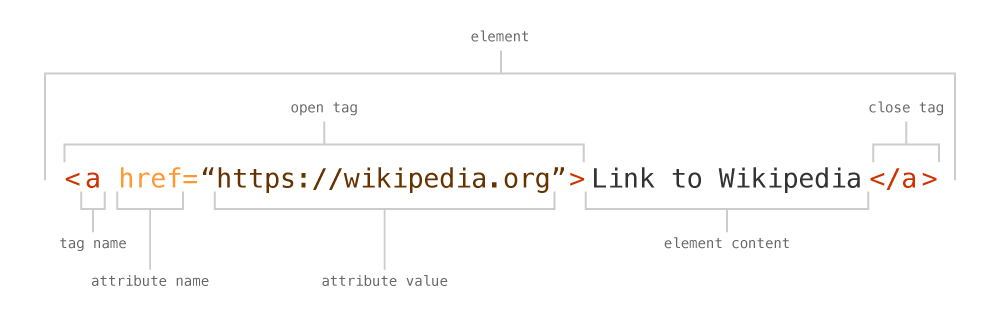

HTML syntax

When writing HTML, the tags used to define the purpose of the text follow a specific syntax.

element— the combination of an open tag, the content, and a close tagopen tag— the part to an element that defines where this type of content startsclose tag— the part of an element that defines where this type of content endsattribute— a piece of metadata that isn’t usually visible in the browser but defines extra information about the element

HTML document setup

To create a valid HTML document we need to put some default code into the file.

Here’s what an empty HTML document looks like:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en-ca"> <!-- Sets the language to Canadian English -->

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title></title>

</head>

<body>

</body>

</html>

<!DOCTYPE html>— The first line of every HTML document should be the doctype. It tells the browser that you’re writing modern HTML.<html>— Wraps the whole HTML file, everything goes inside it.<head>— Stuff that doesn’t necessarily show on the screen, but controls and defines the HTML document.<meta>— Used to tell the browser what kind of characters are used in your document.utf-8allows many languages in the world.<title>— The piece of text that’s shown in the tab of your browser. Also shown in search results as the link.<body>— Not the body of the website, but the body of the HTML document. Everything rendered on the screen in a website goes in here.

All the HTML elements listed below go inside the <body>.

Parent-child relationship

When referring to elements in HTML we talk about them in a parent-child relationship style.

- parent — the element that surrounds this element

- child — the element inside this element, also called a descendant

- sibling — the element beside this element

<!-- <main> is the parent of <h1>, <p> and <dl> -->

<!-- <h1>, <p> and <dl> are all descendants of <main> -->

<main>

<!-- <h1> is a child of <main> -->

<h1>Allosaurus</h1>

<!-- <p> is a child of <main> and a sibling to <h1> -->

<p>A theropod dinosaur from the Late Jurassic period.</p>

<dl>

<!-- <dl> is the <dt> tag's parent -->

<dt>Length</dt>

<!-- <main> is the <dd> tag's grand-parent -->

<dd>9.7 meters</dd>

</dl>

</main>

HTML elements

Each HTML elements as a very specific purpose, here’s a bunch of them.

<p>— paragraph, for defining a chunck of text.

Headings

<h1>— heading level 1, the most important piece of content on the page, every HTML file must have one<h2>— heading level 2, a sub-heading of<h1><h3>— heading level 3, a sub-heading of<h2><h4>— heading level 4, a sub-heading of<h3><h5>— heading level 5, a sub-heading of<h4><h6>— heading level 6, a sub-heading of<h5>

When picking headings, think of an outline, each heading level is a sub heading of the one before. You can’t have an <h3> without and <h2> and you can’t have an <h2> without and <h1>.

An outline of your document with headings might look like this:

<h1>Earth</h1>

<h2>North America</h2>

<h3>Canada</h3>

<h4>Ontario</h4>

<h5>Toronto</h5>

<h5>Ottawa</h5>

<h6>Nepean</h6>

<h6>Kanata</h6>

<h3>United States</h3>

<h4>California</h4>

<h4>New York</h4>

<h2>Africa</h2>

<h3>Egypt</h3>

<h4>Cairo</h4>

<h5>Cairo</h5>

<h3>Nigeria</h3>

<h3>Kenya</h3>

The indentation above is to denote the headings are sub-headings of the one above—not how it should be indented in your code.

Lists

<ul>— unordered list, for when the items inside the list don’t have an order, or the order isn’t important.<ol>— ordered list, for when the items inside the list have an order, or the order is important. Alphabetical, chronological, best to worst.<dl>— description list, when the content of the list has a “term” and a “definition”, like a dictionary.

When writing lists, we have to specifically tell the browser how many items are in the list.

<li>— list item, the tag used to specify a single item in the list

<ul>

<li>T-Rex</li>

<li>Stegosaurus</li>

<li>Apatosaurus</li>

</ul>

The description list is a little different because it needs a tag for the “term” and the “definition”.

<dt>— description term<dd>— description… description

<dl>

<dt>Length</dt>

<dd>12 metres</dd>

<dt>Mass</dt>

<dd>5.4 metric tons</dd>

</dl>

One extra feature that description lists have that <ul> tags and <ol> tags don’t is you can put a <div> directly inside the <dl>.

<dl>

<div>

<dt>Length</dt>

<dd>12 metres</dd>

</div>

<div>

<dt>Mass</dt>

<dd>5.4 metric tons</dd>

</div>

</dl>

You can still put <div> tags (and other tags) inside <ul> and <ol> tags but they must be inside the <li> tags.

Quotes, citations, sources

<q>— quote, for marking up quotes embedded in other things like paragraphs. Often just using quote marks is good enough.<blockquote>— for large, stand alone quotes<cite>— for marking the source of the quote

When marking up blockquotes, the recommended syntax is this:

<blockquote>

<p>Dinosaurs may be extinct from the face of the planet, but they are alive and well in our imaginations.</p>

<footer>— <cite>Steve Miller</cite></footer>

</blockquote>

The <footer> is used to denote that the source of the quote is less important than the quote itself.

Phrasing elements

<em>— for emphasizing text, like is spoken word, to make some words more important<strong>— for even more emphasis than<em><i>— for language elements: text in another language, ship names, sarcasm, irony, movie titles, TV show titles<b>— for keywords; is the word important while searching for the website?

Links

Links

<a>— anchor, for hyperlinks, to link to another page

When adding a link to your site you need to specify where to link to, that’s where we use an attribute.

<!-- Linking to another page in your website that’s in the same folder as this HTML file -->

<a href="other-page.html">Other page</a>

<!-- Linking to another page in your website that’s contained in a folder -->

<a href="dinosuars/trex.html">T-Rex</a>

<!-- Linking to another website, when linking to another website we need the `http` -->

<a href="http://www.wikipedia.org/">Wikipedia</a>

Internal links

To link to another location in the same page we use internal links. We start by adding an ID attribute to an element on the page—the ID is a unique name for that element.

<h2 id="meat-eaters">

Then, in the <a> tag we link directly to the ID:

<a href="#meat-eaters">Meat Eaters</a>

E-mail & telephone links

With HTML you can link e-mail addresses and telephone numbers using alternative schemes.

- For e-mails use

mailto:— this will open the user’s default e-mail client and start a new message. - For phone numbers use

tel:— on mobile phones this will start dialing the number.

Here’s how to link an e-mail address:

<a href="mailto:dinos@extinct.com">dinos@extinct.com</a>

You can also provide a default subject like this:

<a href="mailto:dinos@extinct.com?subject=Dinosaurs%20are%20amazing!">dinos@extinct.com</a>

Notice that all spaces must be escaped as %20 because URLs cannot have spaces in them.

Here’s how you’d link to a telephone number:

<a href="tel:+18005552368">Who you gonna call?</a>

It’s usually best to put the number in the international format, starting with your country code (+1 for North America).

Links

Images & figures

Images in websites are not embedded in the website, but linked to by the HTML document.

<img>— the image tag, to link to an image file so the browser could download it.

Images need two attributes to specify extra details about the image: the location of the image and the alternative content.

<img src="images/trex.jpg" alt="Photo of T-Rex skeleton.">

src— is used to specify where to find the imagealt— is used to describe the image—learn more about the alt attributes

The attributes in HTML tags don’t have to be in a specific order. Reversing the order of the attributes makes no difference to the browser.

<img alt="Photo of T-Rex skeleton." src="images/trex.jpg">

Images with captions

If an image has a caption that describes the image you can surround the image tag with more elements.

<figure>— defining the image as having a caption<figcaption>— marking up the caption itself

<figure>

<img src="images/trex.jpg" alt="">

<figcaption>Photo of T-Rex skeleton in the Ottawa museum.</figcaption>

</figure>

When you have a <figcaption>, the alt attribute can be left empty if the caption does a good job describing the image.

Links

Document elements

<header>— for more important information, like the masthead of the website, where the name and logo and navigation are<nav>— navigation, defining the navigation of the website<footer>— for less important information, like the footer of the website, usually includes the copyright statement, social icons, etc.<main>— for defining the primary content<aside>— for secondary information, stuff that’s not required to understand the primary content, like sidebars, pull quotes, etc.

<!-- The website masthead with the navigation -->

<header>

<h1>Prehistoric creatures</h1>

<!-- The website’s primary navigation -->

<nav>

⋮

</nav>

</header>

<!-- The <main> content of the website: what your user came to see -->

<main>

<h2>Land animals</h2>

⋮

</main>

<!-- Secondary information that’s helpful but not necessary for understanding -->

<aside>

<h2>Prehistoric environment</h2>

⋮

</aside>

<!-- Website footer, copyright information, terms, etc. -->

<footer>

<p>© 1138 Dinosaurs</p>

</footer>

Sections & articles

<section>— for grouping content together that has a heading—there’s no point using a section if it doesn’t have a unique heading<article>— for independent content, stuff that can be removed from this website and would still be understandable, like blog posts & products

Headers & footers in sections & articles

You can put <header> and <footer> and <main> elements inside <article> tags and <section> tags.

The elements can be used to denote the importance of the information inside the article.

<article>

<!-- Denotes more important information inside the article -->

<header>

<h2>Diplodocus stuffed toy</h2>

<p>Super awesome introduction to the toy.</p>

</header>

<!-- Denotes the main content of the article -->

<main>

<p>Lots…</p>

<p>Of…</p>

<p>Details…</p>

</main>

<!-- Denotes secondary, related information -->

<aside>

<h3>Other sauropods</h3>

<ul>

<li>Brachiosaurus</li>

</ul>

</aside>

<!-- Denotes less important information in the article -->

<footer>

<p>Written by a person.</p>

<time datetime="1982-10-28">Published: Today</time>

</footer>

</article>

Links

- HTML5 Doctor: header

- HTML5 Doctor: footer

- HTML5 Doctor: article

- HTML5 Doctor: section

- HTML5 Doctor: aside

Meaningless elements

There are two elements in HTML that don’t add meaning to the content, but can be used as styling hooks, if need to group things together when creating your layout.

<div>— a meaningless group, has restrictions on what elements it can go inside<span>— small runs of meaningless text

<!-- We could use the <span> tag to individually colour all the letters -->

<h1>

<span>R</span>

<span>a</span>

<span>i</span>

<span>n</span>

<span>b</span>

<span>o</span>

<span>w</span>

</h1>

<main>

<!-- Using a <div> as a styling hook: maybe a random coloured box -->

<div>

<h2>Prehistoric creatures</h2>

⋮

</div>

<!-- Another group of elements -->

<div>

<h2>Prehistoric environment</h2>

⋮

</div>

</main>

Break

In HTML there’s an element to add a line break. It should never be used to make space in your website, that’s what CSS is for.

Only use a <br> tag if the line break is part of the content.

A good example is an address. In an address, the formatting of each line is important so a <br> tag is important.

<address>

24 Sussex Drive<br>

Ottawa, ON<br>

K1A 0A3

</address>

Another good example of when to use a <br> tag would be in poems: each stanza is a paragraph, and each line as a break after it.

Horizontal rule

HTML has a tag called the horizontal rule, the <hr> tag. It’s meant to be used as a thematic break in your content.

A great example of a thematic break is from novels: when you’re reading a novel and there is a space between paragraphs, or a little decoration: that’s an <hr>, because it’s a scene break.

The default CSS style, applied by browsers, to <hr> tags is to make it look like a line. Do not use an <hr> to make lines, that’s not its purpose. If you want to make a line, use CSS.

<p>A theropod dinosaur from the Late Jurassic period.</p>

<hr>

<p>The Brontosaurus is now a dinosaur again after many years.</p>

More specific elements

For defining certain types of data and document information.

<time datetime="">— Times, dates, durations; thedatetimeattribute is for the computer readable information<data value="">— Numberical data: weight, length, mass, etc.; thevalueattribute is for the computer readable information<del>— Deleted content<ins>— Newly inserted content<dfn>— A word or term currently being defined<abbr title="">— Abbreviations and acronyms; thetitleattribute is used for the full version<mark>— Highlight text, like in search results<sub>— Subscript<sup>— Superscript

<!-- Distinct points in time-->

<time datetime="1980">Brontosaurus discovery</time>

<time datetime="1980-05-21">Empire Strikes Back released May, 1980</time>

<time datetime="1977-09-05T12:56:00">Voyager 1 launched Sept. 5, 1977 at 12:56</time>

<!-- Time periods -->

<time datetime="P365D">Earth’s orbit around the Sun</time>

<time datetime="PT0H22M">22 minutes to bake cookies</time>

<data value="0.9865">Distance from Earth to Sun: 0.9856 au</data>

The Brontosaurus <data value="15">weighed 15 tonnes</data> & was <data value="22">22 metres long</data>.

<ins datetime="2015">Brontosaurus becomes a valid dinosaur again</ins>

<del datetime="1980-05-21T19:30">See Empire Strikes Back</del>

<p>A <dfn>dinosaur</dfn> was a large prehistoric land reptile.</p>

<abbr title="Hypertext Markup Language">HTML</abbr>

<!-- The current page highlighted in the navigation -->

<a href="#"><mark>Home</mark></a>

<p>Distance from Earth to Sun: 1.476×10<sup>8</sup> km</p>

<p>H<sub>2</sub>O</p>

Entities

Some characters cannot be written in the text content of HTML because the characters are reserved for the HTML syntax.

>— for making greater than symbols<— for making less than symbols&— for writing ampersands — to put a space between words that will never break or word wrap

<p>10 > 9 = yes</p>

<p>600 < 601 = yes</p>

<strong>Big & hairy</strong>

<!-- The unit will never break away from the numbers -->

<p>0.9856 au</p>

Video list

- HTML semantics: Making an HTML file

- HTML semantics: Setting up valid HTML

- HTML semantics: Indentation

- HTML semantics: Headings and paragraphs

- HTML semantics: Lists

- HTML semantics: Quotes and citations

- HTML semantics: Phrasing elements

- HTML semantics: Links

- HTML semantics: Internal links

- HTML semantics: Images & figures

- HTML semantics: Document elements

- HTML semantics: Sections & articles

- HTML semantics: Meaningless elements

- HTML semantics: Break

- HTML semantics: More specific elements

- HTML semantics: Entities